The funds came from two banks he owns, heavily depending on an unforeseen source. According to regulatory records, they took $4.4 billion out of a government programme established during the Great Depression to assist Americans in obtaining mortgages.

Beal is only one of many financiers who use the 11 Federal Home Loan Banks in the country, frequently for purposes unrelated to housing. It isn’t prohibited. However, they stand for what detractors claim are glaring, unresolved issues with the $1.4 trillion system.

Even if they have stopped lending on mortgages, many banks and insurance firms still maintain their balance sheets through memberships in the FHLBs that date back decades. A number of mid-size lenders, such as Signature Bank, Silicon Valley Bank, and First Republic Bank, which failed this year after serving cryptocurrency companies, venture investors, and the very rich, were also supported by the home-loan banks.

Furthermore, during the past ten years, a succession of astute bankers and investors have taken advantage of loopholes to obtain access to the FHLBs and their cheap money. Many of these have at least dabbled in mortgage lending, while some have functioned more like hedge funds or have lent money to well-known people, such as Johnny Depp.

The relationship between home-loan institutions and home lending has come under increased scrutiny from politicians and regulators as millions of Americans struggle to purchase houses.

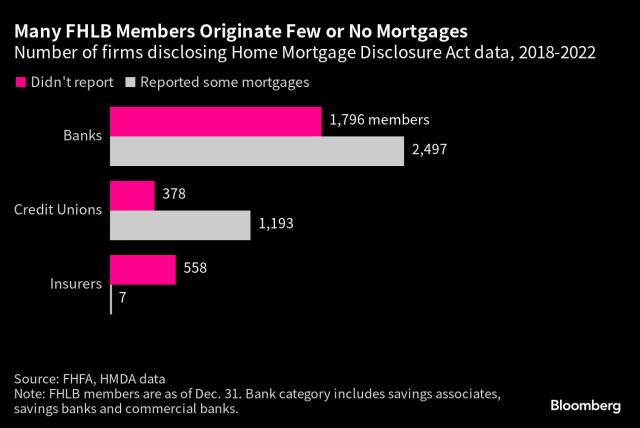

According to a Bloomberg News review of millions of home-lending data given to the government, by the end of last year, 42% of the more than 6,400 banks, credit unions, and insurers that could borrow from the system had not reported making a single mortgage in the previous five years.

For a variety of reasons, many members don’t make large enough loans to buyers to be required to submit the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act’s reporting requirements. Even yet, some businesses can participate in the market indirectly by purchasing loans or mortgage-backed securities that were created elsewhere.

The figures show how the US has not been able to keep up with the significant changes in the mortgage business by modifying its regulations for home-loan banks. Operating under a vague congressional mandate, the FHLBs lend money to a wide variety of financial organisations in order to “promote economical housing finance.” There’s been a lot of leeway for interpretation, so requests to tighten the standards are growing.

Former head of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which oversees home-loan banks, Mark Calabria, said, “Is the membership broader than it needs to be, and does it facilitate lots of activity with little social benefit?” from 2019 to 2021. “It does, and that presents an issue.”

The organisation has been examining FHLBs over the past year in order to suggest updates to the system. Individuals acquainted with the situation have stated that officials have thought about perhaps restricting the amount of money that massive financial institutions may borrow as well as permitting nonbank mortgage lenders to join. However, severe differences in Congress would still need legislators and regulators to carry out new restrictions. Prior to releasing its study, the FHFA declined to comment.

Cheap Money

When lenders were having trouble finding money during the Great Depression, nine decades ago, the FHLB system was established. It was a straightforward idea: mortgage lenders could bring their house loans to local FHLBs, deposit the debts as security, and get further cash “advances” to continue lending.

FHLBs benefit from a number of tax benefits and an implied government guarantee to make sure they have money to distribute at a reasonable price. But their target market is always shifting. Once major home lenders, insurers and savings groups are no longer in this position. A lot of banks withdrew during the financial crisis of 2008. Currently, independent mortgage businesses like Rocket Cos. and UWM Holdings Corp., who are unable to become FHLBs, account for four of the top five US home lenders.

However, members adore the inexpensive and simple fundraising, as Bloomberg has reported, driving advances to a record earlier this year. They can utilise the money for almost anything after receiving it with a range of collateral, including Treasury securities. Additionally, when they join, they usually remain members, regardless if The interest rates on FHLB financing might be more enticing than what many members can get elsewhere, particularly when they need it quickly. The weighted average rate that house loan banks charged was over 1% by the end of 2021. By the end of June, members were losing 4.4% on average due to the money, even after the Fed started a string of rises. Improvements may take a day or thirty years to materialise.

Investors have evolved a variety of tactics to become members throughout time. Some established “captive insurance companies,” which had no customers other than themselves. More recently, businesspeople have established mortgage lenders who meet FHLB requirements by promising to support underserved and minority neighbourhoods. Regulators, however, are becoming more worried about the veracity of certain applicants’ claims.

The FHLBs contend that the fact that the majority of the funds they distribute are supported by loans meant to finance housing is crucial. According to a study that the FHFA put up for Congress last year, principal mortgages on single-family homes and loans for apartment complexes accounted for about 60% of the collateral for advances in 2021. Securities including bundles of home mortgages were linked to even more.

The collateral they promise establishes the relationship to home financing, regardless of how the advances are used, according to Ryan Donovan, CEO of the trade organisation Council of Federal Home Loan Banks. In the end, the home-loan institutions are only abiding with the laws that Congress passed. He went on to say that members “also have to be creditworthy” and that they can only be specific types of financial organisations.

A average banker is not Andy Beal. As a math nerd, he came up with a theory on Fermat’s Last Theorem and offered a $1 million reward to the first person to establish or refute it. He founded a rocketry business. The Professor, the Banker, and the Suicide King: Inside the Richest Poker Game of All Time details the history of his involvement in some of the highest-stakes Texas Hold ’em hands played in Las Vegas in the early 2000s.

His holding company, Beal Financial Corp., is situated in Plano, Texas, and is known as a “FDIC-insured hedge fund” because its banks make non-traditional investments using client deposits that are backed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

It’s an unusual feeling to visit one of his company’s offices. Two employees worked at Beal’s outlet in the affluent Bellevue area of Seattle on a recent Friday afternoon. There were no patrons despite being surrounded by office towers and located across from city hall. With its dark wood, plush seats, and gentle lighting, the atmosphere was serene. A sign listed prices for several savings plans. Mortgages were not available.

The company’s website replicates the restricted products and promotes CLG Hedge Fund, a non-hedge fund entity. It’s a commercial real estate lender associated with Beal. Beal stated in an interview with Bloomberg Markets magazine in 2011 that he gave it that name because he wanted his staff to have the mindset of hedge fund managers, emphasising the most

Sometimes, 70-year-old Beal waits years to seize financing possibilities. In 2001, during the California blackouts, he grabbed power plant distressed debt. He purchased bonds guaranteed by commercial aeroplanes after the aviation sector was severely damaged by the terrorist events of September 11, 2001. Prior to the 2008 housing crisis, he avoided lending money for subprime mortgages and instead bought debt at a reduced cost.

According to a Federal Reserve filing, his company’s assets were around $7.4 billion by the end of 2021. The corporation grew to four times its original size in the previous year, absorbing government debt. In April, MarketWatch revealed that the majority of the purchasing frenzy was concentrated on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, or TIPS. Two primary sources of fresh cash at that time are revealed in regulatory filings from Beal’s banks:

The Federal Home Loan Bank of Dallas criticised the FHLB for the sharp increase in advances, stating in August 2022 that some of the bank’s new, excessive lending was being utilised “to fund investment activities” in its own securities filings.

TIPS helps guard against uncontrollably high inflation, but there’s a catch: when the Fed hikes interest rates, TIPS’s value may decrease. And that is what took place. Since the Fed started raising rates, an index of shorter-dated TIPS, similar to the ones Beal allegedly purchased, has had a negative 1.4% return. As of June 30, Beal’s own banks had depreciated their Treasury securities by 4.5%, or over $1 billion.

According to records, his banks’ outstanding residential real estate loans have decreased 32% to $368 million, or only 1% of assets, since the company began piling up debt at the FHLB.

Beal declined to provide a statement via a representative. The Dallas FHLB indicated through a spokesman that it would not comment on a particular player.

Beal’s FHLB borrowings demonstrate that “he is just making rational, profit-maximizing use” of a readily available funding source, according to Sherrill Shaffer, University of Wyoming’s emeritus professor of financial services. However, Shaffer noted that the action also brought up a crucial query: Should organisations receiving support from the government “be involved in funding individual predictions about macroeconomic conditions”?

When regional banks had difficulties this year, such doubts surfaced over and time again. One of them, Silvergate Bank, has accelerated its expansion by developing a bitcoin industry payments system. Last year, as digital assets fell, its depositors left. In an attempt to match such withdrawals, Silvergate turned to the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco, which at the end of the previous year had advanced $4.3 billion, or over 40% of the company’s assets.

The money belonged to the bank. It possessed a wholesale real estate lending arm, qualified collateral, and had been an FHLB member for over thirty years. However, the bad press the bank received as a result of accepting the payments made the bank’s executives regret their choice, according to a person with knowledge of the situation who wished to remain anonymous while speaking about private discussions. Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, a Democrat, and two other senators urged CEO Alan Lane in a letter towards the end of January, asking if the bank’s advances will be put towards house loans.

The instance demonstrates how the FHLB system functions as an industry shock absorber by giving members rapid, “on-demand liquidity,” according to Teresa Bazemore, president of the San Francisco FHLB. If FHLBs stopped to make decisions about how advancements are utilised, that wouldn’t work, according to her.

One contentious question is whether home-loan institutions ought to be involved in this kind of activity. Last year, former Fed Governor Daniel Tarullo made the case that the system can be an unsustainable crutch for some of its members and that it has had problems borrowing in the bond market during periods of severe financial hardship. Even worse, he continued, the system’s reliance on short-term debt jeopardises other authorities’ efforts to strengthen the financial system.

Access to the low-cost funds offered by home-loan institutions has long been coveted by firms operating on the periphery of the mortgage industry. Following the implementation of new legislation following the 2008 financial crisis, investors devised a plan to acquire access by founding insurance businesses. However, the insurance businesses were little more than shells, serving only the parent companies that had founded them.

The first company to consider joining the home-loan banks was Ladder Capital Corp. Tuebor Captive Insurance Co., a recently established company, joined the FHLB of Indianapolis in 2012. Insurers also entered the system from other investment businesses that gambled on real estate loans, such as Two Harbours Investment Corp., Invesco Mortgage Capital Inc., and Annaly Capital Management Inc.

In 2014, regulators suggested banning the practise, but the Indianapolis FHLB persisted in accepting new players. Big business made up the new members. As of September 30, that year, three captive insurers alone borrowed $2.5 billion, or 13% of its outstanding advances, according to a securities filing.

An official at the bank, John Bingham, stated, “FHLBank Indianapolis has always been and remains in regulatory compliance with membership rules.” Requests for comments from representatives of Ladder, Annaly, Invesco, and Two Harbours went unanswered.

In 2016, the FHFA eventually fixed the gap by requiring insurers who cover third parties to also be members. However, the regulatory body granted the excluded members a five-year period to conclude their debt, thereby providing the enterprises with a financial cushion until 2021.

When mortgage bankers discovered a new method to get membership, the remaining captives continued to borrow from the FHLBs. It had to do with a little-known classification that financial institutions dedicated to helping underprivileged and minority populations received from the Treasury Department.

In order to further that goal, the government released CDFIs from the stringent paperwork standards that banks must adhere to. This allows CDFIs to provide “nonqualified mortgages” to borrowers who would not have been eligible for loans in the first place. As long as they demonstrated their financial stability, it also allowed businesses to get low-cost FHLB borrowing. Investor interest in the programme increased as they received additional benefits.

Advanced financial companies, such as Bayview Asset Management and Fortress Investment Group, started creating CDFIs a few years ago. Only a few months after leaving his position as CEO of Banc of California, California billionaire Steven Sugarman joined the rush in 2017. He established the company that became known as The Change Co.

According to industry journal Scotsman Guide, change is now a key force in the mortgage sector and ranks as the country’s largest generator of nonqualified loans. The company notes on its website that it makes no statements regarding the colour, ethnicity, or income of the underlying debtors and bundles the loans into securities before selling them to investors.

The company does lend to members of ethnic groups, according to mortgage data. But according to property records and people with knowledge of the company’s operations who asked not to be named because they were not authorised to speak publicly about the company’s dealings, Change is also active in some of the most affluent neighbourhoods in California. It made jumbo loans that included financing a home for actor Johnny Depp in the Hollywood Hills.